Designing Your Military Transition

How to find a career that plays to your interests, strengths, and passions while also achieving your financial goals

Disclaimer: This article’s intended audience is officers who already have undergraduate degrees, it may be relevant to veterans who were enlisted, but probably less so.

Leaving the military is often confusing, exciting, terrifying, freeing, lonely, and dizzying all at the same time.

For most officers who spend about four years in college wearing a uniform (especially if you went to an academy) and then four or more years in the military, the prospect of getting out can be quite nerve-racking. One of the largest reasons getting out is so nerve-racking is because you are limited to a known list of options for any major career decision in the military (ie branches or posts). On those lists, it’s pretty easy to then narrow the top couple of choices, which leaves you with only a few options. Most career decisions end up looking like: Hawaii or Germany, pilot or not, Infantry or Armor.

As much as we complain about a lack of choice in the military, it also becomes comforting over time. After all, there’s nothing better than that warm blanket of Tricare Prime. As much as we joke about the military being like prison, this quote from Shawshank Redemption isn’t far from the truth.

These walls are funny. First you hate ’em, then you get used to ’em. After long enough, you get so you depend on ’em. That’s ‘institutionalized.’

— Red

A few choices, to infinite choices, creates panic

So what do most people do when preparing to leave the military and they now have an infinite number of choices for the first time in their life? Well, they probably do what most people do when transitioning from a high degree of certainty to what feels like complete chaos — freak out. They quickly go from an abundance mindset to a scarcity mindset, where they start focusing merely on surviving.

They start haphazardly preparing for a transition two years in advance. They take every random certification under the sun. They seek out the highest-paying jobs they think they can possibly get (often, knowing they will be miserable doing them). They look for jobs most approximate to what they did in the military (even though they may have complained every day about the job that they did). For example, I remember spending weeks trying to figure out how to get a PMP certification, only to find out it was worthless for the career field I wanted to go into.

On the surface, this may seem rational and not that big of a deal. However, as we learn in the military, panic is not a good thing. Panic may create some short-term progress, but often at the expense of your long-term goals. It also creates a lot of stress and wasted effort that could have been spent elsewhere.

The problem with panicking

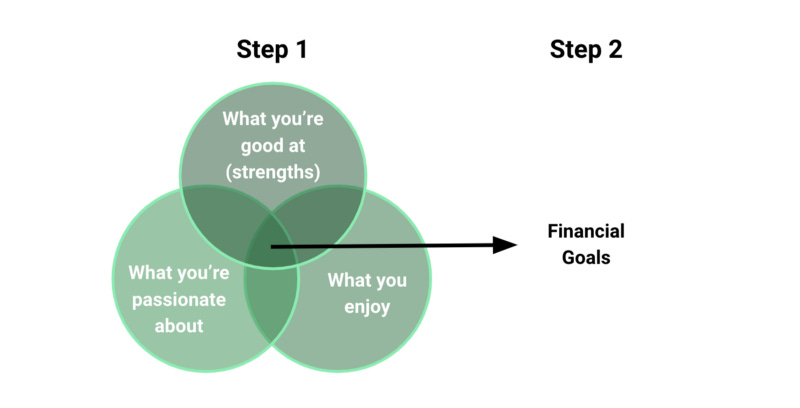

With veterans when it comes to career transition, the most common problem I see is that when they are in this state of panic they put their interests, passions, and strengths in the back seat (or forget about them entirely) to their perceived immediate near-term needs. By ignoring their interests, passions, and strengths they often end up in careers they don’t enjoy and aren’t good at. Ironically, they often end up less financially well off because they are in roles that don’t play to their strengths, passions, or interests.

There is often a fear though, that in prioritizing these three things, they won’t achieve their financial goals. I think your default assumption should be that this is false and you should seek to broaden your horizon and realize there are probably many opportunities that exist where you don’t have to compromise. I think you’ll be amazed at what you find.

So how do you find your dream career?

One of the best guides I’ve found for finding your dream career is the book Designing Your Life. The book helps you uncover careers, which I think the book appropriately calls “lifestyles”, that maximize your interests, strengths, and passions while also meeting your financial goals.

One of my favorite takeaways from the book is the idea of creating lifestyle experiments. Below are some suggested types of lifestyle experiments. Think of lifestyle experiments as conducting a reconnaissance of the world outside of the military.

Conversations with people doing something you might like to do (a “Life Design Interview”)

Shadowing professionals that you’d like to emulate

A one-week unpaid exploratory project that you create

A three-month internship

A scaled-down version of the career you envision (for example, starting a small stand at a farmers market before opening a restaurant)

What I like about the lifestyle experiments is that it was so easy when I was transitioning to come up with ideas about what I thought I would enjoy or what my resume suggested I would be “good” at.

But in reality, they were just ideas and often wrong because I didn’t know much about the world outside the military. By getting out into the real world I was able to learn a lot and experience firsthand what it would be like to live those lifestyles. I didn’t read Designing Your Life until later in the transition but I realized that the process the book described was similar to what I’d been doing.

Getting your ducks in a row before starting your lifestyle experiments

For most lifestyles, before you start doing lifestyle experiments, it’s a good idea to get your resume and especially your LinkedIn looking good as you’ll be reaching out to many new people. The team at Shift has put together a nice article on how to improve your resume and your LinkedIn profile.

A great approach is to ask people you’ll meet if they would be willing to take a look at your resume and provide feedback. This works well because: 1. Everyone loves to help veterans transition out of the military, 2. It is very easy to do and something just about anyone can do, 3. In the process of discussing your resume they will learn a lot about you and they will be able to make better introductions.

An added benefit of this approach is that you’ll start to build relationships with people at these organizations who will help be your advocate on the inside and let you know when opportunities are coming up that are a good fit. They will also help you identify skill gaps and recommend relevant training or education that would help you (thinking about training and education in this light makes it so much easier to prioritize what to do). They can also help you reframe your experiences in a way that will be more easily understood, and thus more meaningful to people in the industry you’re going into.

Of course, your resume will also be much better afterward too. I would note as well each industry seems to have its own flavor for resumes, so focus on getting resume feedback from people in the industry you’re interested in.

Decide which lifestyle experiments to run

In trying to figure out which lifestyles you’re considering, I’d highly recommend going to the Beyond The Uniform website and finding interviews that you find interesting. Beyond The Uniform is a podcast that interviews veterans who’ve successfully transitioned out of the military and are doing just about everything under the sun.

I would also reflect on what experiences in the military gave you the most energy, talk to friends outside of the military who you enjoy spending time with, and what side projects or hobbies were while in the military. The Designing Your Life book goes into great detail on helping narrow down which lifestyle experiments you should run, but those are some ideas.

Especially when you’re leaving a very strong culture like the military, you should really re-evaluate which values and personality traits are truly yours and which ones you’ve just absorbed from the military. Traits absorbed from the military aren’t necessarily good or bad, you just want to be honest with yourself about who you really are and what traits you absorbed to perform in the military, but don’t necessarily want to hold on to in the long run.

In deciding on lifestyle experiments though, the idea isn’t to get it “right” from the start. The primary goal, especially initially, should be to run as many experiments as fast as you can. For example, try to have as many cups of coffee/visit the workplaces with as many people as you can to start. Sometimes it helps to think of it as a game where you’re trying to cross off what you don’t want to do at first instead of figuring out what you do want to do. I remember visiting a veteran who managed an airport for example and quickly learned I had no interest in it. But the time spent wasn’t a waste, it was a great learning opportunity and something to cross off the list.

My lifestyle experiments

Here are the three lifestyles I explored while I was transitioning out of the Army along with how I “ran the experiments” for each.

Going to grad school

I was an International Relations major and still really enjoyed reading books and following current events. I was also interested in businesses and since getting an MBA seems to be a pretty common option after leaving the military I thought both would be good to explore. To start things off, I visited the University of Chicago and sat in on some MBA classes as well as met with faculty in the International Relations department. I left with a sense that although I was interested in International Relations, I didn’t think that I would enjoy it as a career. It didn’t seem to be a good fit for my personality and I wasn’t excited by the career opportunities.

I did continue down the MBA route though and arranged class visits at Stanford’s GSB, Berkley’s Haas, Harvard’s HBS, and others. The experience culminated in attending Tuck NextStep, a 2-week long intro to business fundamentals at the Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. After attending this program and talking with other folks I eventually came to the conclusion that pursuing an MBA wasn’t necessary for the direction that I wanted to go nor a good fit in the near term as I hated sitting in classrooms.

Attending Stanford Ignite further confirmed this, but Stanford Ignite help me realize that I wanted to live in Silicon Valley. I think deciding where to live is one of the most important decisions you’ll make in the military. When it comes to location, I’ve noticed veterans are sometimes averse to moving to large cities because they are often unfamiliar or seen as expensive. But I think there are many more opportunities in large cities and that the higher cost of living is usually made up for with higher wages.

Joining a tech company

Several of my friends from high school went to work at early-stage tech companies and they all really enjoyed what they did. Several of them had worked at more established companies, but often became frustrated with the same things I was frustrated with in the military. My interest in tech companies was further confirmed by attending a Google Resume Workshop, a day-long resume program at a Google campus for veterans. It was an incredible experience as it was unlike any “corporate” environment I’d ever seen - climbing walls, board shorts, laundry, etc. However, I also really liked that it felt like an extremely competitive environment and I liked the mentality of the people I met there.

Leveraging veteran-focused companies to help with running experiments

If you can, I would recommend going through a program like Shift or Breakline which essentially helps you run really efficient lifestyle experiments at companies, but especially tech companies.

Shift.org is especially good if you are still in the military because they leverage the Skillbridge program to set up internships with companies while you’re still in the military.

Breakline offers short courses in Silicon Valley and other cities that help connect veterans with top companies, especially tech companies.

If those aren’t an option, start reaching out to mutual connections on LinkedIn or use LinkedIn to find veterans at the companies you’re interested in. Veterans also get a free year of LinkedIn Premium, now is a good time to start using it.

Founding a tech startup

This is where I ultimately landed. The first lifestyle experiment I ran was going to a Techstars Startup Weekend, a weekend-long program where I pitched my startup idea. Not only did I really enjoy the weekend and the people I was with, but we also won the pitch competition against 10 other teams.

While I walked about from previous experiments with mixed or negative experiences, this was a clear outlier. Not only did I love it, I also seemed to have a natural strength for startups, so I decided to scale up the experiment further. I went to every startup event I could, I went to local meetups, and I started working on my startup on nights and weekends.

When it was time to get out, I’d already significantly de-risked the concept by using the Lean Startup approach. For more about the details of this, I wrote a separate post below 👇.

Another lifestyle experiment I ran was going to Patriot Boot Camp a weekend-long event for active duty, vets, and their spouses. It was experiences like these that further confirmed I really enjoyed the type of people who work on tech startups.

However, with all of that said; I wouldn’t recommend founding a startup right out of the military unless all of the following are true:

A year plus of runway (you have enough savings to not pay yourself for a year)

You have a co-founder (for most veterans starting a tech startup, this means someone who can write code)

Live in Silicon Valley (not required, but strongly suggested)

You think there is a vanishing window of opportunity to start the idea and if you were to start in two years, it would be much more difficult

Note: this list probably doesn’t apply to entrepreneurs starting businesses other than high-growth tech startups.

There simply is a lot of, “you don’t know what you don’t know” when getting out and startups only exacerbate that. If your co-founder isn’t a veteran or hasn’t been in the military for the last couple of years, that is also a great way to reduce risk.

If you are interested in starting your own startup, I think joining an early-stage tech company is often a great way to go and will set you up for success to start your own because you’ll see what right looks like and meet people who may also be interested in starting a startup and complement your skillset (see the previous section on joining a tech company). Shift.org and Breakline are great resources to find startups, you can also use tools like AngelList to find early-stage startups to join.

In conclusion

Transitioning out of the military is often equally exciting as it is terrifying, but you can do it! Transitioning to a job or role where you wake up every morning and enjoy what you’re doing, fits with your strengths, and is something you’re passionate about is possible. There are many roles where you can also achieve your financial goals and not have to compromise on those three circles. The Designing Your Life book is a great guide to executing your transition and running lifestyle experiments to find the intersection of those three circles. Enjoy!